What Mitt Romney Saw in the Senate

Photographs by Yael Malka

This article was featured in One Story to Read Today, a newsletter in which our editors recommend a single must-read from The Atlantic, Monday through Friday.

For most of his life, Mitt Romney has nursed a morbid fascination with his own death, suspecting that it might assert itself one day suddenly and violently.

He controls what he can, of course. He wears his seat belt, and diligently applies sunscreen, and stays away from secondhand smoke. For decades, he’s followed his doctor’s recipe for longevity with monastic dedication—the lean meats, the low-dose aspirin, the daily 30-minute sessions on the stationary bike, heartbeat at 140 or higher or it doesn’t count.

He would live to 120 if he could. “So much is going to happen!” he says when asked about this particular desire. “I want to be around to see it.” But some part of him has always doubted that he’ll get anywhere close.

He has never really interrogated the cause of this preoccupation, but premonitions of death seem to follow him. Once, years ago, he boarded an airplane for a business trip to London and a flight attendant whom he’d never met saw him, gasped, and rushed from the cabin in horror. When she was asked what had so upset her, she confessed that she’d dreamt the night before about a man who looked like him—exactly like him—getting shot and killed at a rally in Hyde Park. He didn’t know how to respond, other than to laugh and put it out of his mind. But when, a few days later, he happened to find himself on the park’s edge and saw a crowd forming, he made a point not to linger.

All of which is to say there is something familiar about the unnerving sensation that Romney is feeling late on the afternoon of January 2, 2021.

It begins with a text message from Angus King, the junior senator from Maine: “Could you give me a call when you get a chance? Important.”

Romney calls, and King informs him of a conversation he’s just had with a high-ranking Pentagon official. Law enforcement has been tracking online chatter among right-wing extremists who appear to be planning something bad on the day of Donald Trump’s upcoming rally in Washington, D.C. The president has been telling them the election was stolen; now they’re coming to steal it back. There’s talk of gun smuggling, of bombs and arson, of targeting the traitors in Congress who are responsible for this travesty. Romney’s name has been popping up in some frightening corners of the internet, which is why King needed to talk to him. He isn’t sure Romney will be safe.

Romney hangs up and immediately begins typing a text to Mitch McConnell, the Senate majority leader. McConnell has been indulgent of Trump’s deranged behavior over the past four years, but he’s not crazy. He knows that the election wasn’t stolen, that his guy lost fair and square. He sees the posturing by Republican politicians for what it is. He’ll want to know about this, Romney thinks. He’ll want to protect his colleagues, and himself.

Romney sends his text: “In case you have not heard this, I just got a call from Angus King, who said that he had spoken with a senior official at the Pentagon who reports that they are seeing very disturbing social media traffic regarding the protests planned on the 6th. There are calls to burn down your home, Mitch; to smuggle guns into DC, and to storm the Capitol. I hope that sufficient security plans are in place, but I am concerned that the instigator—the President—is the one who commands the reinforcements the DC and Capitol police might require.”

McConnell never responds.

I began meeting with Romney in the spring of 2021. The senator hadn’t told anyone he was talking to a biographer, and we kept our interviews discreet. Sometimes we talked in his Senate office, after most of his staff had gone home; sometimes we went to his little windowless “hideaway” near the Senate chamber. But most weeks, I drove to a stately brick townhouse with perpetually drawn blinds on a quiet street a mile from the Capitol.

The place had not been Romney’s first choice for a Washington residence. When he was elected, in 2018, he’d had his eye on a newly remodeled condo at the Watergate with glittering views of the Potomac. His wife, Ann, fell in love with the place, but his soon-to-be staffers and colleagues warned him about the commute. So he grudgingly chose practicality over luxury and settled for the $ 2.4 million townhouse instead.

He tried to make it nice, so that Ann would be comfortable when she visited. A decorator filled the rooms with tasteful furniture and calming abstract art. He planted a garden on the small backyard patio. But his wife rarely came to Washington, and his sons didn’t come either, and gradually the house took on an unkempt bachelor-pad quality. Crumbs littered the kitchen counter; soda and seltzer occupied the otherwise-empty fridge. Old campaign paraphernalia appeared on the mantel, clashing with the decorator’s mid-tone color scheme, and a bar of “Trump’s Small Hand Soap” (a gag gift from one of his sons) was placed in the powder room alongside the monogrammed towels.

In the “dining room,” a 98-inch TV went up on the wall and a leather recliner landed in front of it. Romney, who didn’t have many real friends in Washington, ate dinner alone there most nights, watching Ted Lasso or Better Call Saul as he leafed through briefing materials. On the day of my first visit, he showed me his freezer, which was full of salmon fillets that had been given to him by Lisa Murkowski, the senator from Alaska. He didn’t especially like salmon but found that if he put it on a hamburger bun and smothered it in ketchup, it made for a serviceable meal.

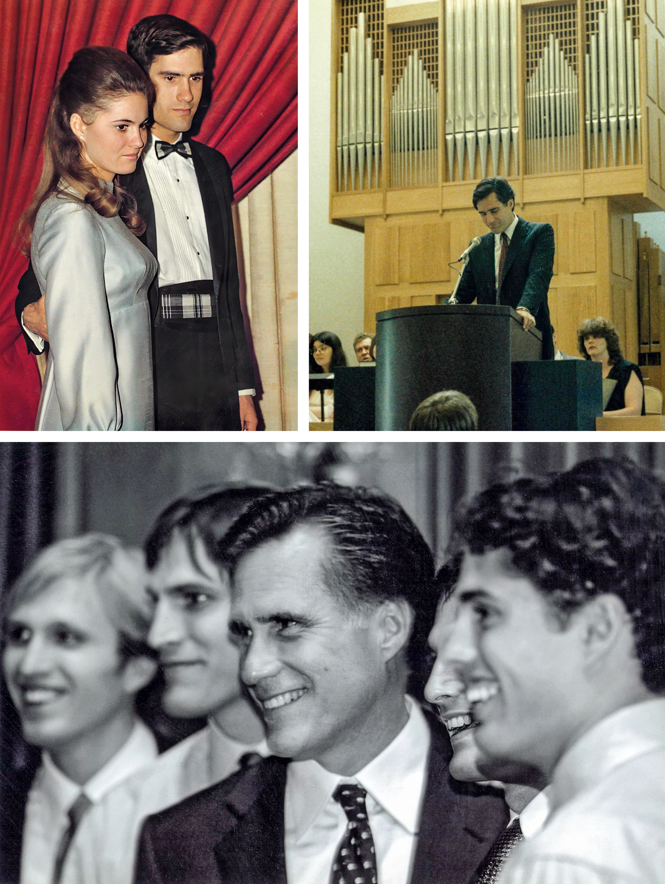

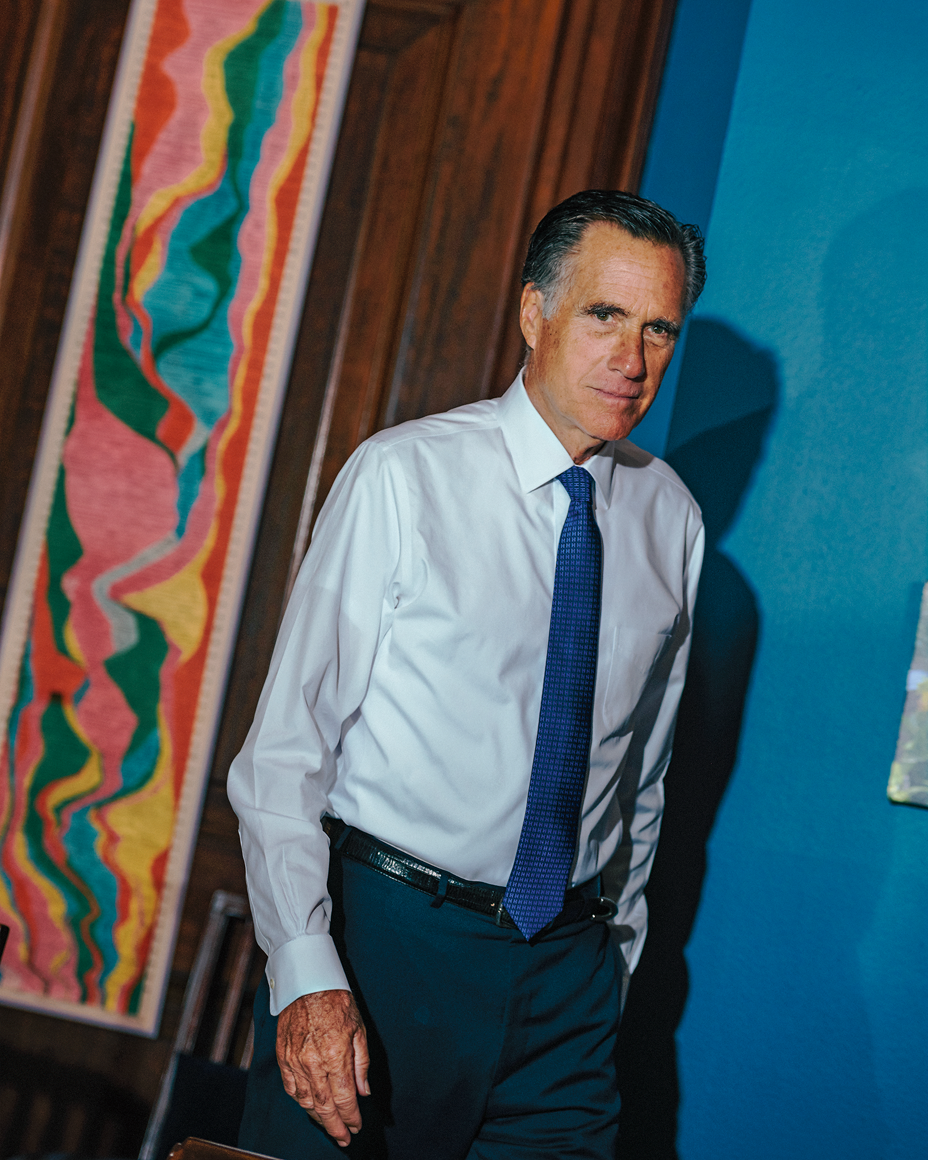

Sitting across from Romney at 76, one can’t help but become a little suspicious of his handsomeness. The jowl-free jawline. The all-seasons tan. The just-so gray at the temples of that thick black coif, which his barber once insisted he doesn’t dye. It all seems a little uncanny. Only after studying him closely do you notice the signs of age. He shuffles a little when he walks now, hunches a little when he sits. At various points in recent years, he’s gotten so thin that his staff has worried about him. Mostly, he looks tired.

Romney’s isolation in Washington didn’t surprise me. In less than a decade, he’d gone from Republican standard-bearer and presidential nominee to party pariah thanks to a series of public clashes with Trump. What I didn’t quite expect was how candid he was ready to be. He instructed his scheduler to block off evenings for weekly interviews, and told me that no subject would be off-limits. He handed over hundreds of pages of his private journals and years’ worth of personal correspondence, including sensitive emails with some of the most powerful Republicans in the country. When he couldn’t find the key to an old filing cabinet that contained some of his personal papers, he took a crowbar to it and deposited stacks of campaign documents and legal pads in my lap. He’d kept all of this stuff, he explained, because he thought he might write a memoir one day, but he’d decided against it. “I can’t be objective about my own life,” he said.

Some nights he vented; other nights he dished. He’s more puckish than his public persona suggests, attuned to the absurdist humor of political life and quick to share stories that others might consider indiscreet. I got the feeling he liked the company—our conversations sometimes stretched for hours.

“A very large portion of my party,” he told me one day, “really doesn’t believe in the Constitution.” He’d realized this only recently, he said. We were a few months removed from an attempted coup instigated by Republican leaders, and he was wrestling with some difficult questions. Was the authoritarian element of the GOP a product of President Trump, or had it always been there, just waiting to be activated by a sufficiently shameless demagogue? And what role had the members of the mainstream establishment—people like him, the reasonable Republicans—played in allowing the rot on the right to fester?

I had never encountered a politician so openly reckoning with what his pursuit of power had cost, much less one doing so while still in office. Candid introspection and crises of conscience are much less expensive in retirement. But Romney was thinking beyond his own political future.

Earlier this year, he confided to me that he would not seek reelection to the Senate in 2024. He planned to make this announcement in the fall. The decision was part political, part actuarial. The men in his family had a history of sudden heart failure, and none had lived longer than his father, who died at 88. “Do I want to spend eight of the 12 years I have left sitting here and not getting anything done?” he mused. But there was something else. His time in the Senate had left Romney worried—not just about the decomposition of his own political party, but about the fate of the American project itself.

Shortly after moving into his Senate office, Romney had hung a large rectangular map on the wall. First printed in 1931 by Rand McNally, the “histomap” attempted to chart the rise and fall of the world’s most powerful civilizations through 4,000 years of human history. When Romney first acquired the map, he saw it as a curiosity. After January 6, he became obsessed with it. He showed the map to visitors, brought it up in conversations and speeches. More than once, he found himself staring at it alone in his office at night. The Egyptian empire had reigned for some 900 years before it was overtaken by the Assyrians. Then the Persians, the Romans, the Mongolians, the Turks—each civilization had its turn, and eventually collapsed in on itself. Maybe the falls were inevitable. But what struck Romney most about the map was how thoroughly it was dominated by tyrants of some kind—pharaohs, emperors, kaisers, kings. “A man gets some people around him and begins to oppress and dominate others,” he said the first time he showed me the map. “It’s a testosterone-related phenomenon, perhaps. I don’t know. But in the history of the world, that’s what happens.” America’s experiment in self-rule “is fighting against human nature.”

“This is a very fragile thing,” he told me. “Authoritarianism is like a gargoyle lurking over the cathedral, ready to pounce.”

For the first time in his life, he wasn’t sure if the cathedral would hold.

Optimism—quaint in retrospect, though perhaps delusional—is what first propelled Romney to the Senate. It was 2017. Trump was president, and the early months of his tenure had been a predictable disaster; the Republican Party was in trouble. Romney’s friends were encouraging him to get back in the game, and he was tempted by the open Senate seat in Utah, a state where Trump was uniquely unpopular among conservative voters. On his iPad, he typed out the pros and cons of running—high-minded sentiments about public service in one column, lifestyle considerations in the other. Then, at the top of the list, he wrote a line from Yeats that he couldn’t get out of his mind: “The best lack all conviction, while the worst / Are full of passionate intensity.”

To Romney, this was the problem with the Trump-era GOP. He believed there were still decent, well-intentioned leaders in his party—they were just nervous. They needed a nudge. A role model, perhaps. As the former nominee, he told me, he felt that he “had the potential to be an alternative voice for Republicans.”

Five years earlier, while running for president, Romney had accepted Trump’s endorsement. At the time, he’d rationalized the decision—yes, Trump was a buffoon and a conspiracy theorist, but he was just a guy on reality TV, not a serious political figure. Romney now realized that he’d badly underestimated the potency of Trumpism. But in the summer of 2017, it still seemed possible that the president would be remembered as an outlier.

Two days before he was sworn in as a senator, Romney published an op-ed in The Washington Post designed to signal his independence from Trump. “On balance,” Romney wrote, the president “has not risen to the mantle of the office.” He pledged to work with him when they agreed on an issue, to oppose him when they didn’t, and to speak out when necessary. He thought of this as a new way to be a Republican senator in Trump’s Washington.

His colleagues were not impressed. A few days after Romney was sworn in, Politico ran a story about the “chilly reception” he was receiving from his fellow Republican senators. The story quoted several of them, on the record or anonymously, griping about his unwillingness to get along with the leader of their party. Romney emailed the story to his advisers, describing himself as “the turd in the punch bowl.” “These guys have got to justify their silence, at least to themselves.”

Romney had spent the weeks since his election typing out a list of all the things he wanted to accomplish in the Senate. By the time he took office, it contained 42 items and was still growing. The legislative to-do list ranged from complex systemic reforms—overhauling immigration, reducing the national deficit, addressing climate change—to narrower issues such as compensating college athletes and regulating the vaping industry. His staff was bemused when he showed it to them; even in less polarized, less chaotic times, the kind of ambitious agenda he had in mind would be unrealistic. But Romney was not deterred. He told his aides he wanted to set up meetings with all 99 of his colleagues in his first six months, and began studying a flip-book of senators’ pictures so that he could recognize his potential legislative partners.

In one early meeting, a colleague who’d been elected a few years earlier leveled with him: “There are about 20 senators here who do all the work, and there are about 80 who go along for the ride.” Romney saw himself as a workhorse, and was eager for others to see him that way too. “I wanted to make it clear: I want to do things,” he told me.

He quickly became frustrated, though, by how much of the Senate was built around posturing and theatrics. Legislators gave speeches to empty chambers and spent hours debating bills they all knew would never pass. They summoned experts to appear at committee hearings only to make them sit in silence while they blathered some more.

As the weeks passed, Romney became fascinated by the strange social ecosystem that governed the Senate. He spent his mornings in the Senate gym studying his colleagues like he was an anthropologist, jotting down his observations in his journal. Richard Burr walked on the treadmill in his suit pants and loafers; Sherrod Brown and Dick Durbin pedaled so slowly on their exercise bikes that Romney couldn’t help but peek at their resistance settings: “Durbin was set to 1 and Brown to 8. 🙂 :). My setting is 15—not that I’m bragging,” he recorded.

He joked to friends that the Senate was best understood as a “club for old men.” There were free meals, on-site barbers, and doctors within a hundred feet at all times. But there was an edge to the observation: The average age in the Senate was 63 years old. Several members, Romney included, were in their 70s or even 80s. And he sensed that many of his colleagues attached an enormous psychic currency to their position—that they would do almost anything to keep it. “Most of us have gone out and tried playing golf for a week, and it was like, ‘Okay, I’m gonna kill myself,’ ” he told me. Job preservation, in this context, became almost existential. Retirement was death. The men and women of the Senate might not need their government salary to survive, but they needed the stimulation, the sense of relevance, the power. One of his new colleagues told him that the first consideration when voting on any bill should be “Will this help me win reelection?” (The second and third considerations, the colleague continued, should be what effect it would have on his constituents and on his state.)

Perhaps Romney’s most surprising discovery upon entering the Senate was that his disgust with Trump was not unique among his Republican colleagues. “Almost without exception,” he told me, “they shared my view of the president.” In public, of course, they played their parts as Trump loyalists, often contorting themselves rhetorically to defend the president’s most indefensible behavior. But in private, they ridiculed his ignorance, rolled their eyes at his antics, and made incisive observations about his warped, toddlerlike psyche. Romney recalled one senior Republican senator frankly admitting, “He has none of the qualities you would want in a president, and all of the qualities you wouldn’t.”

This dissonance soon wore on Romney’s patience. Every time he publicly criticized Trump, it seemed, some Republican senator would smarmily sidle up to him in private and express solidarity. “I sure wish I could do what you do,” they’d say, or “Gosh, I wish I had the constituency you have,” and then they’d look at him expectantly, as if waiting for Romney to convey profound gratitude. This happened so often that he started keeping a tally; at one point, he told his staff that he’d had more than a dozen similar exchanges. He developed a go-to response for such occasions: “There are worse things than losing an election. Take it from somebody who knows.”

One afternoon in March 2019, Trump paid a visit to the Senate Republicans’ weekly caucus lunch. He was in a buoyant mood—two days earlier, the Justice Department had announced that the much-anticipated report from Special Counsel Robert Mueller failed to establish collusion between the Trump campaign and Russia during the 2016 election. As Romney later wrote in his journal, the president was met with a standing ovation fit for a conquering hero, and then launched into some rambling remarks. He talked about the so-called Russia hoax and relitigated the recent midterm elections and swung wildly from one tangent to another. He declared, somewhat implausibly, that the GOP would soon become “the party of health care.” The senators were respectful and attentive.

As soon as Trump left, Romney recalled, the Republican caucus burst into laughter.

Few of his colleagues surprised him more than Mitch McConnell. Before arriving in Washington, Romney had known the Senate majority leader mainly by reputation. With his low, cold mumble and inscrutable perma-frown, McConnell was viewed as a win-at-all-costs tactician who ruled his caucus with an iron fist. Observing him in action, though, Romney realized that McConnell rarely resorted to threats or coercion—he was primarily a deft manager of egos who excelled at telling each of his colleagues what they wanted to hear. This often left Romney guessing as to which version of McConnell was authentic—the one who did Trump’s bidding in public, or the one who excoriated him in their private conversations.

In the fall of 2019, Trump’s efforts to pressure Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky into investigating the Biden family’s business dealings were revealed in the press. Romney called the scheme “wrong and appalling,” and Trump responded with a wrathful series of tweets that culminated with a call to #IMPEACHMITTROMNEY. A few weeks later, Romney read in the press that McConnell had privately urged Trump to stop attacking members of the Senate. Romney thanked McConnell for sticking up for him against Trump.

“It wasn’t for you so much as for him,” McConnell replied. “He’s an idiot. He doesn’t think when he says things. How stupid do you have to be to not realize that you shouldn’t attack your jurors?

“You’re lucky,” McConnell continued. “You can say the things that we all think. You’re in a position to say things about him that we all agree with but can’t say.” (A spokesperson said that McConnell does not recall this conversation and that he was “fully aligned” with Trump during the impeachment trial.)

As House Democrats pursued their impeachment case against the president, Romney carefully studied his constitutional role in the imminent Senate trial. He read and reread Alexander Hamilton’s treatise on impeachment, “Federalist No. 65.” He pored over the work of constitutional scholars and reviewed historical definitions of “high crimes and misdemeanors.” His understanding was that once the House impeached a president, senators were called on to set aside their partisan passions and act as impartial jurors.

Meanwhile, among Romney’s Republican colleagues, rank cynicism reigned. They didn’t want to hear from witnesses; they didn’t want to learn new facts; they didn’t want to hold a trial at all. During an interview with CNN, Lindsey Graham frankly admitted that he was “not trying to pretend to be a fair juror here,” and predicted that the impeachment process would “die quickly” once it reached the Senate.

On December 11, 2019, McConnell summoned Romney to his office and pitched him on joining forces. He explained that several vulnerable members of their caucus were up for reelection, and that a prolonged, polarizing Senate trial would force them to take tough votes that risked alienating their constituents. McConnell wanted Romney to vote to end the trial as soon as the opening arguments were completed. McConnell didn’t bother defending Trump’s actions. Instead, he argued that protecting the GOP’s Senate majority was a matter of vital national importance. He predicted that Trump would lose reelection, and painted an apocalyptic picture of what would happen if Democrats took control of Congress: They’d turn Puerto Rico and D.C. into states, engineering a permanent Senate majority; they’d ram through left-wing legislation such as Medicare for All and the Green New Deal. Romney said he couldn’t make any promises about his vote. (McConnell declined to comment on this conversation.)

A week later, Republican senators met for their regular caucus lunch. Romney had come to dread these meetings. They had a certain high-school-cafeteria quality that made him feel ill at ease. “I mean, it’s a funny thing,” he told me. “You don’t want to be the only one sitting at the table and no one wants to sit with you.” He had always had plenty of friends growing up, but his religion often made him feel like he didn’t quite fit in. At Cranbrook prep school, in Michigan, he was the only Mormon on campus; at Stanford, he would go to bars with his friends and drink soda. Walking into those caucus lunches each week—deciding whom to sit with, and whether to speak up—Romney felt his differentness just as acutely as he had in his teens.

The meeting was being held shortly before Christmas break, and Romney hoped the caucus would get some guidance on what to expect from the trial. Instead, he was dismayed to learn that the featured guest was Vice President Mike Pence, who was there to talk through the White House’s defense strategy. “Stunning to me that he would be there,” Romney grumbled in his journal. “There is not even an attempt to show impartiality.” (Romney had long been put off by Pence’s pious brand of Trump sycophancy. No one, he told me, has been “more loyal, more willing to smile when he saw absurdities, more willing to ascribe God’s will to things that were ungodly than Mike Pence.”)

[From the January/February 2018 issue: McKay Coppins on God’s plan for Mike Pence]

At the next meeting, McConnell told his colleagues they should understand that the upcoming trial was not really a trial at all. “This is a political process,” he said—and it was thus appropriate for them to behave like politicians. “If impeachment is a partisan political process, then it might as well be removed from the Constitution,” Romney recalled muttering to Ted Cruz and Mike Lee, who were seated near him. The senators politely ignored him.

Two articles of impeachment arrived at the Senate on January 15, 2020, and the trial began. Romney did his best to be a model juror—he took notes, parsed the arguments, and agonized each night in his journal over how he should vote. “Interestingly, sometimes I think I will be voting to convict, and sometimes I think I will vote to exonerate,” he wrote on January 23. “I jot down my reasons for each, but when I finish, I begin to consider the other side of the argument … I do the same thing—with less analysis of course—in bed. That’s probably why I’m not sleeping more than 4 or 5 hours.”

The other members of his caucus didn’t seem quite so burdened. They mumbled dismissive comments while the impeachment managers presented their case. He heard some of them literally cheer for Trump’s defense team. Maybe Romney was naive, but he couldn’t get over how irresponsible it all seemed. “How unlike a real jury is our caucus!” he wrote in his journal.

And yet, to at least some of his fellow Republicans, the case against Trump was compelling—even if they’d never say so in public. During a break in the proceedings, after the impeachment managers finished their presentation, Romney walked by McConnell. “They nailed him,” the Senate majority leader said.

Romney, taken aback by McConnell’s candor, responded carefully: “Well, the defense will say that Trump was just investigating corruption by the Bidens.”

“If you believe that,” McConnell replied, “I’ve got a bridge I can sell you.” (McConnell said he does not recall this conversation and it does not match his thinking at the time.)

By the time the defense wrapped up its arguments, on January 28, Romney was privately leaning toward acquittal. In his journal, he rationalized the vote—Trump hadn’t explicitly told Zelensky he would withhold military aid until an investigation was open—but he also admitted a self-interested motive. “I do not at all want to vote to convict,” he wrote. “The consequences of doing so are too painful to contemplate.”

When he informed his senior staff of his thinking the next morning, he detected a palpable sense of relief. Maybe their boss still had a future in Republican politics after all. Romney’s wife, though, seemed less elated by the news. Ann didn’t argue with him. She didn’t render any judgment at all. She just said she was “surprised.” Romney, who’d organized much of his life around winning and keeping Ann’s respect, couldn’t help but wonder if she meant something more.

On January 30, the senators were allowed to question lawyers on both sides of the impeachment case. Late in the day, a question submitted by Graham caught Romney’s attention: Even if Trump really had done exactly what the House accused him of, he asked, “isn’t it true that the allegations still would not rise to the level of an impeachable offense?” Trump’s lawyers concurred.

The answer stunned Romney. Until then, Trump’s defense had been that he wasn’t really trying to shake down a world leader for political favors by threatening to withhold military aid. Now, it seemed to Romney, Trump’s lawyers were effectively arguing that such a shakedown would have been fine. Allowing that argument to go unchallenged would set a dangerous precedent. When the Senate recessed, Romney returned to his office to go over the facts of the case again. The gravity of the moment was catching up to him. Finally, Romney knelt on the floor and prayed.

A few days earlier, Romney had paid a visit to Senator Joe Manchin’s houseboat, Almost Heaven—the West Virginian’s home in Washington. The impeachment trial had presented a serious political quandary for Manchin, a moderate Democrat whose state Trump had carried with 68 percent of the vote in 2016. While the voters there liked Manchin’s independence, they wouldn’t be happy if he voted to convict. After listening to Manchin describe his predicament, Romney offered his take: “We’re both 72. We should probably be thinking about oaths and legacy, not just reelection.”

Now it was time for Romney to follow his own advice. Writing in his journal, he once again laid out the facts of the case as he understood them. Hundreds of words, page after page, he wrote and wrote and wrote, until finally the truth was clear to him: Trump was guilty.

Romney slept fitfully that night, rising at 4 a.m. to review the case one more time. Still convinced of the president’s guilt, he opened up a laptop at his kitchen table and wrote the first draft of the speech he’d eventually give on the Senate floor.

After that, he made his way to the Russell Building, where he broke the news to his senior staff. Some were surprised but approving; others were distressed. One staffer simply put her head in her hands. She didn’t speak or look up again for the rest of the meeting.

Shortly before 2 p.m. on the day of the vote, Romney left his office and walked to the Capitol, where he waited in his hideaway for his turn to speak. Minutes before going on the floor, he received an unexpected call on his cellphone. It was Paul Ryan. Romney and his team had kept a tight lid on how he planned to vote, but somehow his former running mate had gotten word that he was about to detonate his political career. Romney had been less judgmental of Ryan’s acquiescence to Trump than he’d been of most other Republicans’. He believed Ryan was a sincere guy who’d simply misjudged Trump.

And yet, here was Ryan on the phone, making the same arguments Romney had heard from some of his more calculating colleagues. Ryan told him that voting to convict Trump would make Romney an outcast in the party, that many of the people who’d tried to get him elected president would never speak to him again, and that he’d struggle to pass any meaningful legislation. Ryan said that he respected Romney, and wanted to make absolutely sure he’d thought through the repercussions of his vote. Romney assured him that he had, and said goodbye.

He walked onto the Senate floor and read the remarks he’d written at his kitchen table. “As a Senator-juror,” Romney began, “I swore an oath before God to exercise impartial justice. I am profoundly religious. My faith is at the heart of who I am—” His voice broke, and he had to pause as emotion overwhelmed him. “I take an oath before God as enormously consequential.”

Romney acknowledged that his vote wouldn’t change the outcome of the trial—the Republican-led Senate would fall far short of the 67 votes needed to remove the president from office, and he would be the lone Republican to find Trump guilty. Even so, he said, “with my vote, I will tell my children and their children that I did my duty to the best of my ability, believing that my country expected it of me.”

He would never feel comfortable at a Republican caucus lunch again.

Early on the morning of January 6, 2021, Romney slid into the back of an SUV and began the short ride to his Senate office, with a Capitol Police car in tow. Ann had begged him not to return to Washington that day. She had a bad feeling about all of this. In the year since his impeachment vote, her husband had become a regular target of heckling and harassment from Trump supporters. They shouted “traitor” from car windows and confronted him in restaurants. Romney had tried to make light of her concern: “If I get shot, you can move on to a younger, more athletic husband.” A special police escort had been arranged for him that morning. But now, as he looked out the window at the streets of D.C., he found himself wondering about its utility. If somebody wants to shoot me, he thought, what good is it to have these guys in a car behind me?

He tried to go about his morning as usual, but he struggled to concentrate. Two miles away, at the White House Ellipse, thousands of angry people were gathering for a “Save America” rally.

The Senate chamber is a cloistered place, with no television monitors or electronic devices, and strict rules that keep outsiders off the floor. So when the Senate convened that afternoon to debate his colleagues’ objection to certifying the 2020 electoral votes, Romney didn’t know exactly what was happening outside. He didn’t know that the president had just directed his supporters to march down Pennsylvania Avenue—“We’re going to the Capitol!” He didn’t know that pipe bombs had been discovered outside both parties’ nearby headquarters. He didn’t know that Capitol Police were scrambling to evacuate the Library of Congress, or that rioters were crashing into police barricades outside the building, or that officers were beginning to realize they were outnumbered and wouldn’t be able to hold the line much longer.

At 2:08 p.m., Romney’s phone buzzed with a text message from his aide Chris Marroletti, who had been communicating with Capitol Police: “Protestors getting closer. High intensity out there.” He suggested that Romney might want to move to his hideaway.

Romney looked around the chamber. The hideaway was a few hundred yards and two flights of stairs away. He didn’t want to leave if he didn’t have to. He’d stay put, he decided, unless the protesters got inside the building.

A minute later, Romney’s phone buzzed again.

“They’re on the west front, overcame barriers.”

Adrenaline surging, Romney stood and made his way to the back of the chamber, where he pushed open the heavy bronze doors. He was expecting the usual crowd of reporters and staff aides, but nobody was there. A strange, unsettling quiet had engulfed the deserted corridor. He turned left and started down the hall toward his hideaway, when suddenly he saw a Capitol Police officer sprinting toward him at full speed.

“Go back in!” the officer boomed without breaking stride. “You’re safer inside the chamber.”

Romney turned around and started to run.

He got back in time to hear the gavel drop and see several men—Secret Service agents, presumably—rush into the chamber without explanation and pull the vice president out. Then, all at once, the room turned over to chaos: A man in a neon sash was bellowing from the middle of the Senate floor about a security breach. Officials were scampering around the room in a panic, slamming doors shut and barking at senators to move farther inside until they could be evacuated.

Something about the volatility of the moment caused Romney—

a walking amalgam of prep-school manners and Mormon niceness and the practiced cool of the private-equity set—to lose his grip, and he finally vented the raw anger he had been trying to contain. He turned to Josh Hawley, who was huddled with some of his right-wing colleagues, and started to yell. Later, Romney would struggle to recall the exact wording of his rebuke. Sometimes he’d remember shouting “You’re the reason this is happening!” Other times, it would be something more terse: “You did this.” At least one reporter in the chamber would recount seeing the senator throw up his hands in a fit of fury as he roared, “This is what you’ve gotten, guys!” Whatever the words, the sentiment was clear: This violence, this crisis, this assault on democracy—this is your fault.

Soon, Romney was being rushed down a hallway with several of his colleagues. The mob was only one level below, so they couldn’t take the stairs; instead, the senators piled into elevators, 10 at a time, while the rest loitered anxiously in the hallway.

When they reached the basement, Romney asked a pair of police officers, “Where are we supposed to go?”

“The senators know,” one of the officers replied.

Marroletti, Romney’s aide, spoke up: “These are the senators. They don’t know. Where are we supposed to go?”

Romney was mystified by the ineptitude, but he knew the situation wasn’t the police’s fault. He thought about the text message he’d sent to McConnell a few days earlier explicitly warning of this scenario. How were they not ready for this? It was, in some ways, a perfect metaphor for his party’s timorous, shortsighted approach to the Trump era. As a boy, he’d read Idylls of the King with his mother; now he could understand the famous quote from Tennyson’s Guinevere as she witnesses the consequences of corruption in Arthur’s court: “This madness has come on us for our sins.”

Eventually the senators made it to a safe room. There were no chairs at first, so the shell-shocked legislators simply wandered around, murmuring variations of “I can’t believe this is happening.” When someone wheeled in a TV and turned on CNN, the senators got their first live look at the sacking of the Capitol. A sickened silence fell over the room as anger and outrage were replaced by dread. To Romney, the Senate chamber was a sacred place. Watching it transform into a playground for violent, costumed insurrectionists was almost too much to bear.

The National Guard finally dispersed the crowd and secured the Capitol. As the Senate prepared to reconvene late that night, Romney took solace in assuming that his most extreme colleagues now realized what their ruse had wrought, and would abandon their plan to object to the electors. Romney had written a speech a few days earlier condemning their procedural farce, but now he was thinking of tossing it. Surely the point was moot.

But to Romney’s astonishment, the architects of the plan still intended to move forward. When Hawley stood to deliver his speech, Romney was positioned just behind the Missourian’s right shoulder, allowing a C‑SPAN camera to capture his withering glare.

What bothered Romney most about Hawley and his cohort was the oily disingenuousness. “They know better!” he told me. “Josh Hawley is one of the smartest people in the Senate, if not the smartest, and Ted Cruz could give him a run for his money.” They were too smart, Romney believed, to actually think that Trump had won the 2020 election. Hawley and Cruz “were making a calculation,” Romney told me, “that put politics above the interests of liberal democracy and the Constitution.”

When it was Romney’s turn to speak, he wasted little time before laying into his colleagues. “What happened here today was an insurrection, incited by the president of the United States,” Romney said. “Those who choose to continue to support his dangerous gambit by objecting to the results of a legitimate, democratic election will forever be seen as being complicit in an unprecedented attack against our democracy.” His voice sharpened when he addressed the patronizing claim that objecting to the certification was a matter of showing respect for voters who believed the election had been stolen. It struck Romney that, for all their alleged populism, Hawley and his allies seemed to take a very dim view of their Republican constituents.

“The best way we can show respect for the voters who are upset is by telling them the truth!” Romney said, his voice rising to a shout.

Before sitting down, he posed a question to his fellow senators—a question that, whether he realized it or not, he’d been wrestling with himself for nearly his entire political career. “Do we weigh our own political fortunes more heavily than we weigh the strength of our republic, the strength of our democracy, and the cause of freedom? What is the weight of personal acclaim compared to the weight of conscience?”

[From the January/February 2022 issue: Barton Gellman on Donald Trump’s next insurrection]

For a blessed moment after January 6, it looked to Romney as if the fever in his party might finally be breaking. GOP leaders condemned the president and denounced the rioters. Trump, who was booted from Twitter and Facebook for fear that he might use the platforms to incite more violence, saw his approval rating plummet. New articles of impeachment were introduced, and McConnell’s office leaked to the press that he was considering a vote to convict. Federal law enforcement began sifting through hundreds of hours of amateur footage from January 6 to identify and arrest the people who had stormed the Capitol. Joe Biden was sworn in as the 46th president of the United States, and Trump—who skipped the inauguration—flew off to Florida, where he seemed destined for a descent into political irrelevance and legal trouble.

But the Republicans’ flirtation with repentance was short-lived. Within months, Fox News was offering a revisionist history of January 6 and recasting the rioters as martyrs and victims of a vengeful, overreaching Justice Department. The House Republican leader, Kevin McCarthy, who’d initially blamed Trump for the riot, paid a visit to Mar-a-Lago to mend his relationship with the ex-president.

Some of the reluctance to hold Trump accountable was a function of the same old perverse political incentives—elected Republicans feared a political backlash from their base. But after January 6, a new, more existential brand of cowardice had emerged. One Republican congressman confided to Romney that he wanted to vote for Trump’s second impeachment, but chose not to out of fear for his family’s safety. The congressman reasoned that Trump would be impeached by House Democrats with or without him—why put his wife and children at risk if it wouldn’t change the outcome? Later, during the Senate trial, Romney heard the same calculation while talking with a small group of Republican colleagues. When one senator, a member of leadership, said he was leaning toward voting to convict, the others urged him to reconsider. You can’t do that, Romney recalled someone saying. Think of your personal safety, said another. Think of your children. The senator eventually decided they were right.

As dismayed as Romney was by this line of thinking, he understood it. Most members of Congress don’t have security details. Their addresses are publicly available online. Romney himself had been shelling out $ 5,000 a day since the riot to cover private security for his family—an expense he knew most of his colleagues couldn’t afford.

By the time Democrats proposed a bipartisan commission to investigate the events of January 6, the GOP’s 180 was complete. Virtually every Republican in Congress came out in full-throated opposition to the idea. Romney, who’d been consulting with historians about how best to preserve the memory of the insurrection—he’d proposed leaving some of the damage to the Capitol unrepaired—was disappointed by his party’s posture, but he was no longer surprised. He had taken to quoting a favorite scene from Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid when he talked about his party’s whitewashing of the insurrection—twisting his face into an exaggerated expression before declaring, “Morons. I’ve got morons on my team!” To Romney, the revisionism of January 6 was almost worse than the attack itself.

In spring 2021, Romney was invited to speak at the Utah Republican Party convention, in West Valley City. Suspecting that some in the crowd might boo him, he came up with a little joke to defuse the tension. As soon as he went onstage, he’d ask the crowd of partisans, “What do you think of President Biden’s first 100 days?” When they booed in response, he’d say, “I hope you got that out of your system!”

But when Romney took the stage, he quickly realized that he’d underestimated the level of vitriol awaiting him. The heckling and booing were so loud and sustained that he could barely get a word out. As he labored to push through his prepared remarks, he became fixated on a red-faced woman in the front row who was furiously screaming at him while her child stood by her side. He paused his speech.

“Aren’t you embarrassed?” he couldn’t help but ask her from the stage.

Afterward, Romney tried to reframe it as a character-building experience—a moment in which he got to live up to his father’s example. When he was young, Mitt had watched an audience stacked with auto-union members vociferously boo his dad during a governor’s debate. George had been undeterred. “He was proud to stand for what he believed,” Romney told me. “If people aren’t angry at you, you really haven’t done anything in public life.”

But there was also something unsettling about the episode. As a former presidential candidate, he was well acquainted with heckling. Scruffy Occupy Wall Streeters had shouted down his stump speeches; gay-rights activists had “glitter bombed” him at rallies. But these were Utah Republicans—they were supposed to be his people. Model citizens, well-behaved Mormons, respectable patriots and pillars of the community, with kids and church callings and responsibilities at work. Many of them had probably been among his most enthusiastic supporters in 2012. Now they were acting like wild children. And if he was being honest with himself, there were moments up on that stage when he was afraid of them.

“There are deranged people among us,” he told me. And in Utah, “people carry guns.”

“It only takes one really disturbed person.”

He let the words hang in the air for a moment, declining to answer the question his confession begged: How long can a democracy last when its elected leaders live in fear of physical violence from their constituents?

In some ways, Romney settled most fully into his role as a senator once Trump was gone. He joined a bipartisan “gang” of lawmakers who actually seemed to enjoy legislating, and helped pass a few bills he was proud of.

He even tried to work productively within his caucus. Romney drew a distinction between the Republican colleagues he viewed as sincerely crazy and those who were faking it for votes. He was open, for instance, to partnering with Senator Ron Johnson of Wisconsin, the conspiracy-spouting, climate-change-denying, anti-vax Trump disciple, because while he could be exasperating—once, Romney told me, after listening to an extended lecture on Hunter Biden’s Ukrainian business dealings, he blurted, “Ron, is there any conspiracy you don’t believe?”—you could at least count on his good faith. What Romney couldn’t stomach any longer was associating himself with people who cynically stoked distrust in democracy for selfish political reasons. “I doubt I will work with Josh Hawley on anything,” he told me.

But as Romney surveyed the crop of Republicans running for Senate in 2022, it was clear that more Hawleys were on their way. Perhaps most disconcerting was J. D. Vance, the Republican candidate in Ohio. “I don’t know that I can disrespect someone more than J. D. Vance,” Romney told me. They’d first met years earlier, after he read Vance’s best-selling memoir, Hillbilly Elegy. Romney was so impressed with the book that he hosted the author at his annual Park City summit in 2018. Vance, who grew up in a poor, dysfunctional family in Appalachia and went on to graduate from Yale Law School, had seemed bright and thoughtful, with interesting ideas about how Republicans could court the white working class without indulging in toxic Trumpism. Then, in 2021, Vance decided he wanted to run for Senate, and reinvented his entire persona overnight. Suddenly, he was railing against the “childless left” and denouncing Indigenous Peoples’ Day as a “fake holiday” and accusing Joe Biden of manufacturing the opioid crisis “to punish people who didn’t vote for him.” The speed of the MAGA makeover was jarring.

“I do wonder, how do you make that decision?” Romney mused to me as Vance was degrading himself on the campaign trail that summer. “How can you go over a line so stark as that—and for what?” Romney wished he could grab Vance by the shoulders and scream: This is not worth it! “It’s not like you’re going to be famous and powerful because you became a United States senator. It’s like, really? You sell yourself so cheap?” The prospect of having Vance in the caucus made Romney uncomfortable. “How do you sit next to him at lunch?”

By the spring of 2023, Romney had made it known to his inner circle that he very likely wouldn’t run again. He’d been leaning this way for at least a year but had kept it to himself. There were practical reasons for the coyness: He didn’t want to start hemorrhaging staffers or descend into lame-duck irrelevance. But some close to Romney wondered if he was simply being stubborn. Several Utah Republicans were already lining up to run for his seat, and the talk in political circles was that he’d struggle to win another primary. Romney, who couldn’t stand the idea of being put out to pasture, insisted that stepping down was his call. “I’ve invested a lot of money already in my political fortunes,” he told me, “and if I needed to do so again to win the primary, I would.”

But he was now at an age when he had to ruthlessly guard his time. He still had books he wanted to write, still dreamed of teaching. He wanted to spend time with Ann while they were both healthy.

Yet even as he made up his mind to leave the Senate, he struggled to walk away from politics entirely. Trump was running again, after all. The crisis wasn’t over. For months, people in his orbit—most vocally, his son Josh—had been urging him to embark on one last run for president, this time as an independent. The goal wouldn’t be to win—Romney knew that was impossible—but to mount a kind of protest against the terrible options offered by the two-party system. He also wanted to ensure that someone onstage was effectively holding Trump to account. “I was afraid that Biden, in his advanced years, would be incapable of making the argument,” he told me.

Romney relished the idea of running a presidential campaign in which he simply said whatever he thought, without regard for the political consequences. “I must admit, I’d love being on the stage with Donald Trump … and just saying, ‘That’s stupid. Why are you saying that?’ ” He nursed a fantasy in which he devoted an entire debate to asking Trump to explain why, in the early weeks of the pandemic, he’d suggested that Americans inject bleach as a treatment for COVID-19. To Romney, this comment represented the apotheosis of the former president’s idiocy, and it still bothered him that the country had simply laughed at it and moved on. “Every time Donald Trump makes a strong argument, I’d say, ‘Remind me again about the Clorox,’ ” Romney told me. “Every now and then, I would cough and go, ‘Clorox.’ ”

Romney almost went through with it, this maximally disruptive, personally cathartic primal scream of a presidential campaign. But he abandoned it once he realized that he’d most likely end up siphoning off votes from the Democratic nominee and ensuring a Trump victory. So, in April, Romney pivoted to a new idea: He privately approached Joe Manchin about building a new political party. They’d talked about the prospect before, but it was always hypothetical. Now Romney wanted to make it real. His goal for the yet-unnamed party (working slogan: “Stop the stupid”) would be to promote the kind of centrist policies he’d worked on with Manchin in the Senate. Manchin was himself thinking of running for president as an independent, and Romney tried to convince him this was the better play. Instead of putting forward its own doomed candidate in 2024, Romney argued, their party should gather a contingent of like-minded donors and pledge support to the candidate who came closest to aligning with its agenda. “We’d say, ‘This party’s going to endorse whichever party’s nominee isn’t stupid,’ ” Romney told me.

He acknowledged that this plan wasn’t foolproof, that maybe he’d be talked out of it. The last time we spoke about it, he was still in the brainstorming stage. What he seemed to know for sure was that he no longer fit in his current party. Throughout our two years of interviews, I heard Romney muse repeatedly about leaving the GOP. He’d stayed long after he stopped feeling at home there—long after his five sons had left—because he felt a quixotic duty to save it. This meld of moral responsibility and personal hubris is, in some ways, Romney’s defining trait. When he’s feeling sentimental, he attributes the impulse to the “Romney obligation,” and talks about the deep commitment to public service he inherited from his father. When he’s in a more introspective mood, he talks about the surge of adrenaline he feels when he’s rushing toward a crisis.

But it was hard to dispute that the battle for the GOP’s soul had been lost. And Romney had his own soul to think about. He was all too familiar with the incentive structure in which the party’s leaders were operating. He knew what it would take to keep winning, the things he would have to rationalize.

“You say, ‘Okay, I better get closer to this line, or maybe step a little bit over it. If I don’t, it’s going to be much worse,’ ” he told me. You can always convince yourself that the other party, or the other candidate, is bad enough to justify your own decision to cross that line. “And the problem is that line just keeps on getting moved, and moved, and moved.”

This article was adapted from McKay Coppins’s book Romney: A Reckoning. It appears in the November 2023 print edition with the headline “What Mitt Romney Saw in the Senate.”